Kathmandu, Jan 28: Nepal has made improvement to reduce hunger with a score of 19.1 in the 2022 Global Hunger Index (GHI), a drop from 21.2 in 2014.

The country is ranked 81st out of the 121 countries, ahead of some South Asian countries, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. However, it is behind Sri Lanka which is ranked 64th with 13.6 points. India’s position has depleted because it fell to 107th position with 29.1 points. Similarly, Bangladesh is ranked 84th with 19.6, while Pakistan 99th with 26.1. Afghanistan is ranked 1.9th with 29.9.

The GHI report was published jointly by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe amid a function here organised by the NGO Federation of Nepal. The index less than 10 points reflect low hunger, and between 10 and 19.9 moderate hunger. Similarly, from 20 to 34.9 indicates serious hunger, and from 35 to 49.9 alarming. Above 50 reveals extremely alarming.

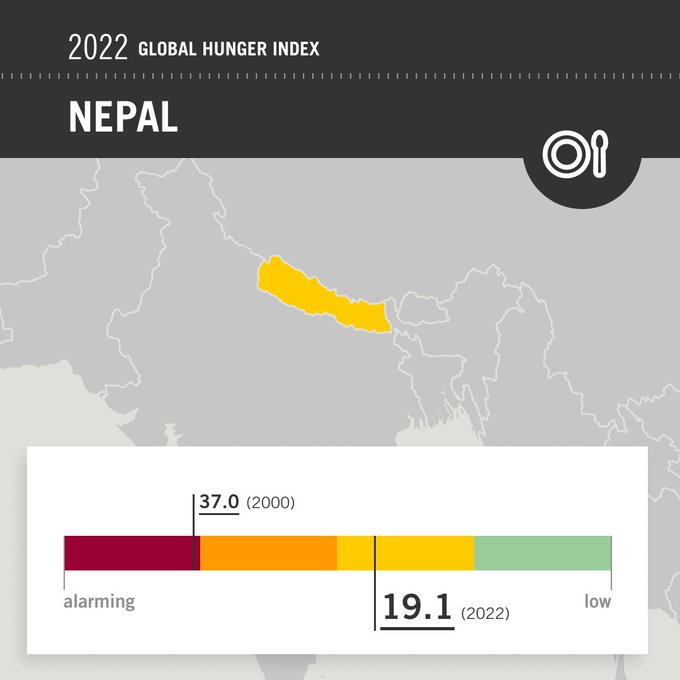

The aim of the GHI is to trigger action to end hunger around the world, it has been shared. As the 2022 Global Hunger Index (GHI) shows, Nepal scoring 19.1 on the GHI signifies that it has a moderate level of hunger. It has continued to do improvements on the GHI scores over the past 22 years. Nepal scored 37 on the GHI Trend in 2000. The score dropped to 30 in 2007, 21.2 in 2014 and 19.1 in 2022.

Although Nepal has done some progress in reducing hunger, it is not satisfactory, said Dr Yamuna Ghale, food security expert. GHI scores are calculated based on a formula combining four indicators—undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality—that together capture the multidimensional nature of hunger, she said.

When we look at data of stunting rates regionally, there is a grim picture, she said. Stunting rates vary across the provinces with the range of 22.6 and 22.9 percent in Gandaki and Bagmati Provinces respectively, and the figure jumps to more than double being at 47.8 percent in Karnali Province. This is not a matter of satisfaction, she said.

Likewise, children consuming foods rich in iron and iron supplements are low across provinces. According to her, Province 1 and 2 have the lowest percentage in the case of women and children respectively. Women and children in Province 1 and 2 were also found the most anemic in the country, which could be due to less or no iron intakes, she said.

Cooperation, coordination and collaboration among related stakeholders, ensuring localised, sustainable, inclusive and resilient food system and understanding relevant stakeholders in the realisation of human rights to food could be a way out, she suggested.

Similarly, alignment with legal provisions including gender responsiveness, establishment of responsive institutions, capacitating legislators and the government and ensuring target provisions like gender, geography, vulnerabilities, emergencies and market shocks could be pathways, according to her.