Todd G. Buchholz

SAN DIEGO, Sept 11 (PS): A movie starring Helen Mirren as Golda Meir has just opened, 50 years after the war that ended the Israeli prime minister’s career. More snore than sleeper hit, Golda captures its subject’s Chesterfield chain-smoking while brushing past a timely lesson about diplomacy: to be effective, leaders need to know each other’s personalities as well as each other’s national interests.

America, for its part, has blundered when presidents have confused the two. President Barack Obama thought he understood Syrian President Bashar al-Assad when Obama warned him that using chemical weapons would cross a “red line.” Assad scoffed and used them anyway. Smelling weakness, Russian President Vladimir Putin all but goose-stepped into Crimea.

Donald Trump then conflated his personal rapport with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un with policy, crowing that a “beautiful” letter from the dictator had changed the dynamic of US-North Korea relations. And President Joe Biden thought he had a handle on the Taliban when he ordered US troops to vacate Afghanistan. He didn’t, and America’s hasty departure left deadly Black Hawk and Apache choppers in the hands of a barbarous regime.

What about Meir? An immigrant to the United States from Russia, she could have enjoyed a comfortable life in Milwaukee. The valedictorian of her high school class, she once organized a fundraiser to buy books for poor refugee children. But instead of pursuing comfort, she moved to Tel Aviv in 1921 and slogged through Israel’s difficult early history.

Meir was in Israel for the drought that sent farmers begging for drops of water. She held a fellow civilian as he died from a gunshot wound. And she witnessed British soldiers turning away Holocaust survivors who would end up back in detainment camps.

Meir had deep-set bags under her eyes – as if to prove what she had seen. When sworn in as Israel’s prime minister in 1969, she looked remarkably like the exhausted Lyndon Johnson who had just stepped down from the US presidency (give or take a foot and a half in height).

Male Zionists could be chauvinistic. The comedian Jackie Mason once joked that Israeli men looked so tan and macho that he was sure they must be Puerto Ricans. But Meir refused to be relegated to the women’s section of any meeting. She became a key adviser to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who called her “the best man in my cabinet.”

After Israel declared independence in 1948, Ben-Gurion asked Meir to oversee the defense of Jerusalem and food distribution. She imposed daily rationing of just three ounces of dried fish, lentils, macaroni, and beans. Sleep-deprived, she frequently ran the gauntlet from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. One day, while bullets strafed her bus, she covered her eyes. When asked why, she replied: “I’m not really afraid to die. … But how will I live if I’m blinded? How will I work?” A few days later, her bus was ambushed while careening around a curve just outside Jerusalem. The man next to her died in her lap.

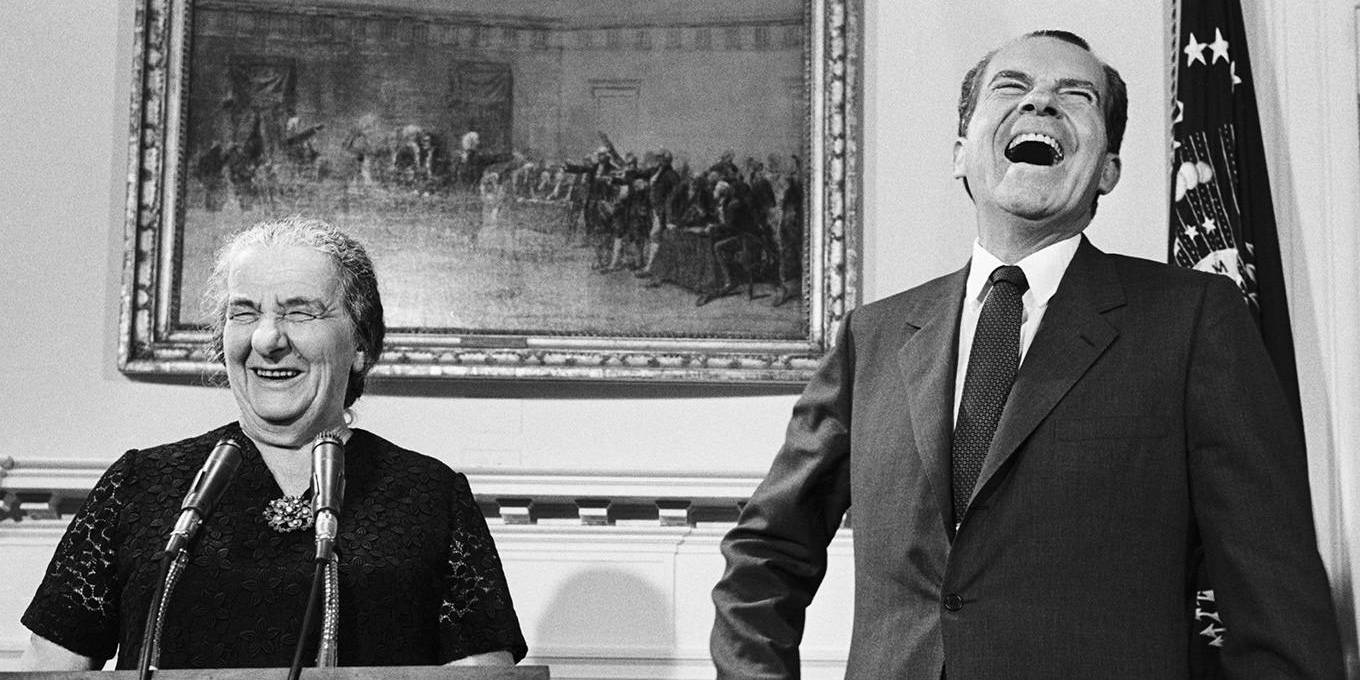

Smart, strong men found her appealing. US President Richard Nixon, overcoming his psychological demons, showed her his seldom-seen warm side. He also overrode Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to fulfill Meir’s wartime requests as prime minister.

Kissinger had dithered over helping Israel during the surprise 1973 Yom Kippur attack, when Egyptian forces crippled the Israeli Air Force with new Soviet anti-aircraft and antitank missiles. Nixon finally said, “Look, Henry, we’re going to get just as much blame for sending three as if we send thirty or a hundred… so send everything that flies.”

Even more fascinating were Meir’s close ties with the kings of Jordan, Abdullah and his grandson Hussein, whom she met with secretly for frank and friendly conversations. Just before Israel declared independence, she snuck to the Jordanian border, put on a black dress and a veil, and rode with the king’s driver to a safe house in the hills. “Why are the Jews in such a hurry to have a state?” the king asked her. “We’ve waited two thousand years. That’s not my definition of a hurry,” she replied.

When Hussein later became king, he developed a strong personal relationship with Meir. In 1970, he asked her to direct the Israeli Air Force to destroy Syrian tanks amassed on Jordan’s border, and the Syrians retreated under the threats. He also sometimes snuck into Israel to see her, piloting his own Bell helicopter and landing at a rendezvous point near the Dead Sea. Just days before the Yom Kippur war in 1973, he flew to a Mossad safe house to warn her of a possible attack. She and Hussein regretted that he did not have enough sway to hammer out a broad Israeli-Arab peace agreement. Heavy losses in the 1973 war cost her the premiership.

Four years later, when Egypt’s Anwar Sadat made his courageous trip to Israel and told the cheering Knesset that “we truly welcome you to live among us in peace,” Meir waited in the receiving line. They bussed cheeks and joked about becoming grandparents. Years earlier, Meir had been convinced that Sadat could be a peacemaker. In that moment, a year before her death from cancer, she was finally proved right.

Todd G. Buchholz, a former White House director of economic policy and managing director of the Tiger Management hedge fund, is the author of New Ideas from Dead Economists (Plume, 2021) and The Price of Prosperity (Harper, 2016), and co-author of the musical Glory Ride.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023.

www.project-syndicate.org