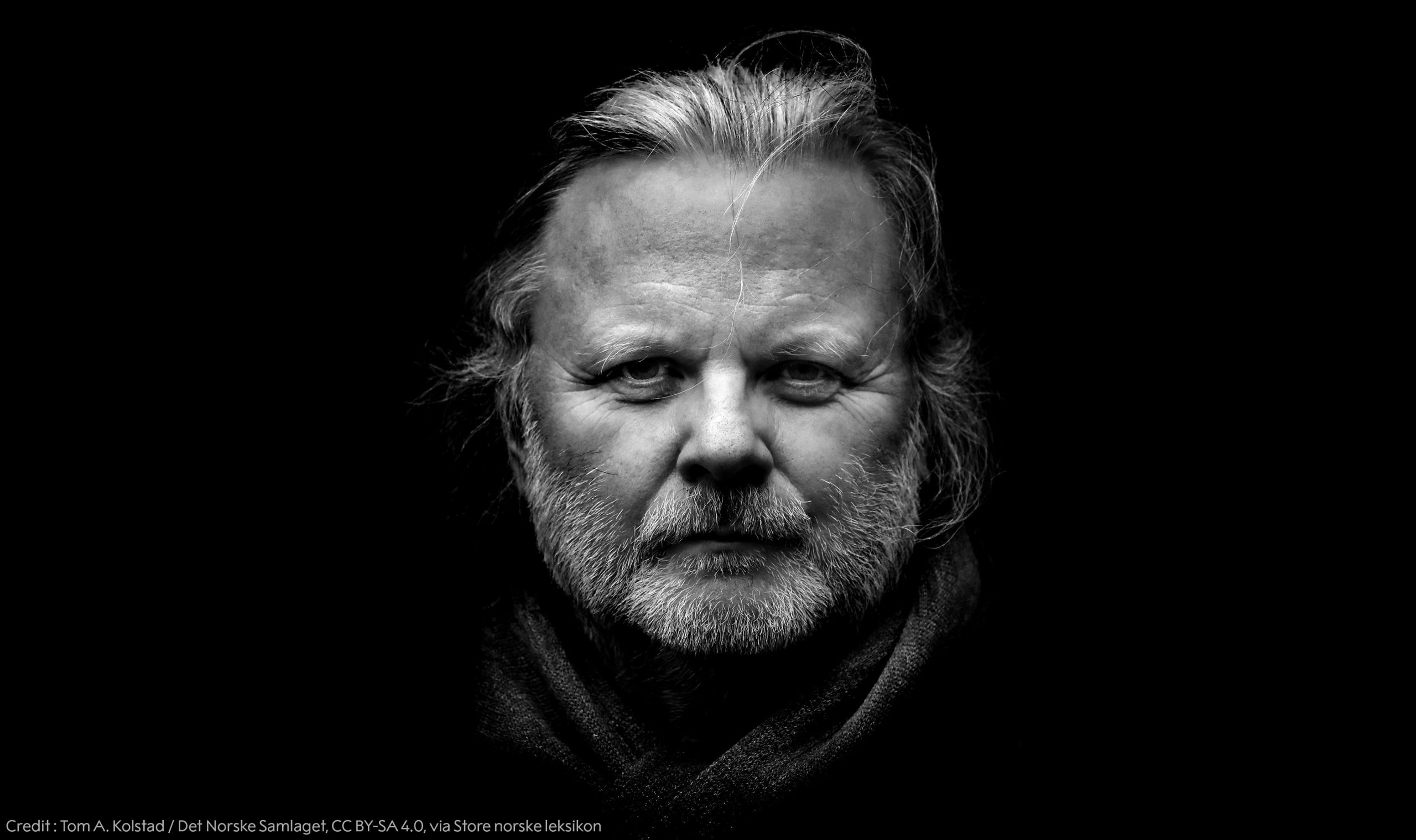

STOCKHOLM, Oct 5 (AP) — Jon Fosse, a master of spare Nordic writing in a sprawling body of work ranging from plays to novels and children’s books, won the Nobel Prize in literature on Thursday for works that “give voice to the unsayable.”

Fosse’s work, which is rooted in his Norwegian background, “focuses on human insecurity and anxiety,” Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel literature committee, told The Associated Press. “The basic choices you make in life, very elemental stuff.”

One of his country’s most-performed dramatists, Fosse said he had “cautiously prepared” himself for a decade to receive the news that he had won.

“I was surprised when they called, yet at the same time not,” Fosse, 64, told Norwegian public broadcaster NRK. “It was a great joy for me to get the phone call.”

The author of 40 plays as well as novels, short stories, children’s books, poetry and essays, Fosse was honored “for his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable,” according to the Swedish Academy, which awards the prize.

Fosse has cited the bleak, enigmatic work of Irish writer Samuel Beckett — the 1969 Nobel literature laureate — as an influence on his minimalist style.

His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, and his debut play, “Someone is Going to Come,” in 1992. His major prose works include “Melancholy;” “Morning and Evening,” whose two parts depict a birth and a death; “Wakefulness;” and “Olav’s Dreams.”

His plays, which have been staged across Europe and in the United States, include “The Name,” “Dream of Autumn” and “I am the Wind.” His work “A New Name: Septology VI-VII” — described by Olsson as Fosse’s “magnum opus” — was a finalist for the International Booker Prize in 2022.

Fosse has also taught writing — one of his students was best-selling Norwegian novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard — and consulted on a Norwegian translation of the Bible.

Mats Malm, permanent secretary of the academy, reached Fosse by telephone to inform him of the win. He said the writer was driving in the countryside and promised to drive home carefully.

Fosse is the fourth Norwegian writer to get the literature prize, but the first in nearly a century. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson got it in 1903, Knut Hamsun was awarded it in 1920 and Sigrid Undset in 1928.

Fosse writes in Nynorsk, one of the two official written standards of Norwegian that is chiefly spoken in and around Bergen, where the writer lives. It is used by just 10% of Norway’s 5.4 million people, according to the Language Council of Norway, but completely intelligible with the other written form, Bokmaal.

Guy Puzey, senior lecturer in Scandinavian Studies at the University of Edinburgh, said Bokmaal is “the language of power, it’s the language or urban centers, of the press,” while Nynorsk is used mainly by people in rural western Norway.

“So it’s a really big day for a minority language,” he said.

In recognition of his contribution to Norwegian culture, Fosse was granted use of an honorary residence in the grounds of the Royal Palace owned by the Norwegian state.

“A great recognition of outstanding authorship that makes an impression and touches people all over the world,” Norway’s Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter. “All of Norway offers congratulations and is proud today!”

In a statement released by his publishing house, Samlaget, Fosse said he saw the prize “as an award to the literature that first and foremost aims to be literature, without other considerations.”

The Nobel Prizes carry a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million) from a bequest left by their creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel. Winners also receive an 18-carat gold medal and diploma at the award ceremonies in December.

Last year, French author Annie Ernaux won the prize for what the prize-giving Swedish Academy called “the courage and clinical acuity” of books rooted in her small-town background in the Normandy region of northwest France.

Ernaux was just the 17th woman among the 119 Nobel literature laureates. The literature prize has long faced criticism that it is too focused on European and North American writers, as well as too male-dominated.

In 2018, the award was postponed after sex abuse allegations rocked the Swedish Academy, which names the Nobel literature committee, and sparked an exodus of members. The academy revamped itself but faced more criticism for giving the 2019 award to Austria’s Peter Handke, who has been called an apologist for Serbian war crimes.

Who is Jon Fosse?

Biobibliography

Jon Fosse was born 1959 in Haugesund on the Norwegian west coast. His immense œuvre written in Nynorsk and spanning a variety of genres consists of a wealth of plays, novels, poetry collections, essays, children’s books and translations. While he is today one of the most widely performed playwrights in the world, he has also become increasingly recognized for his prose. His debut novel Raudt, svart 1983, as rebellious as it was emotionally raw, broached the theme of suicide and, in many ways, set the tone for his later work.

Fosse’s European breakthrough as a dramatist came with Claude Régy’s 1999 Paris production of his play Nokon kjem til å komme (1996; Someone Is Going to Come, 2002). Even in this early piece, with its themes of fearful anticipation and crippling jealousy, Fosse’s singularity is fully evident. In his radical reduction of language and dramatic action, he expresses the most powerful human emotions of anxiety and powerlessness in the simplest everyday terms. It is through this ability to evoke man’s loss of orientation, and how this paradoxically can provide access to a deeper experience close to divinity, that he has come to be regarded as a major innovator in contemporary theatre.

In common with his great precursor in Nynorsk literature Tarjei Vesaas, Fosse combines strong local ties, both linguistic and geographic, with modernist artistic techniques. He includes in his Wahlverwandschaften such names as Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard and Georg Trakl. While Fosse shares the negative outlook of his predecessors, his particular gnostic vision cannot be said to result in a nihilistic contempt of the world. Indeed, there is great warmth and humour in his work, and a naïve vulnerability to his stark images of human experience.

In his second novel Stengd gitar (1985), Fosse presents us with a harrowing variation on one of his major themes, the critical moment of irresolution. A young mother leaves her flat to throw rubbish down the chute but locks herself out, with her baby still inside. Needing to go and seek help, she is unable to do so since she cannot abandon her child. While she finds herself, in Kafkaesque terms, ‘before the law’, the difference is clear: Fosse presents everyday situations that are instantly recognizable from our own lives. As with his first book, the novel is heavily pared down to a style that has come to be known as ‘Fosse minimalism’. At the same time, there is a sense of trepidation and a powerful ambivalence. This later comes to feature in his dramatic work, in which he is able to make use of pauses and interruptions to express this uncertainty – and moreover charge them with emotion. In his plays, we are confronted with words or acts that appear incomplete, a lack of resolution that continues to preoccupy our minds. The play Natta syng sine songar (1998; Nightsongs, 2002) represents a drawn-out yet unresolved quandary in which the woman’s impulse to go off with a new man is constantly opposed by a counter-impulse – a ‘yes’ qualified with the keyword ‘but’. The man she has abandoned ends up taking his own life, while her new beau disappears from sight. It is no doubt Fosse’s courage in opening himself up to the uncertainties and anxieties of everyday life that lies behind the extraordinary recognition he has received among the general public.

From the very beginning of the play Namnet from 1995 (The Name, 2002), we are presented with an emotionally charged everyday situation. A girl, young and pregnant, is waiting for the father of the unborn child, who has been delayed. The tension is immediately built up here due to this sense of uncertainty and its resulting fragmentary sentences. These disruptions moreover create a gulf between the girl’s longing for a new life with her child and her anxiety that she has been abandoned by the father.

Something similar occurs in the heart-rending work Dødsvariasjonar (2002; Death Variations, 2004), a one-act play about a girl who commits suicide, told backwards from the time of her death. It is written in short, interrupted locutions delivered by six nameless characters from different generations, both alive and dead. The piece ends with the daughter’s deeply moving speech, delivered from the other side of the grave, in which she expresses a fundamental uncertainty as to whether her decision to take her own life was the correct one.

In Skuggar (2007), Fosse stages a series of reunions during which the same simple phrases are repeated with an explicit ambiguity: ‘No, of course / That’s just what you say when you meet someone’. As a dramatist, Fosse generally respects unity of place while disrupting unity of time. In fact, the place where the nameless characters meet after many years is both unknown to them and rather disconcerting. This timeless setting of Fosse’s own creation provides an emblematic backdrop for his dramatic encounters. In his earlier play Draum om hausten (1999; Dream of Autumn, 2004), he presents us with a masterly representation of multi-layered time. The scene here is a cemetery where a man – coincidentally, it seems – meets a woman. In fact they have spent their lives together, a shared experience filled with love, false steps and unrealized dreams. Also in this piece, different time layers in which the demons of the past haunt the living are almost seamlessly intertwined.

A notable example of his early prose is the short novel Morgon og kveld from 2000 (Morning and Evening, 2015). Written in the midst of an intense period of dramatic output, it may well be his most hopeful work. One morning, the elderly protagonist Johannes’s perception of reality begins to dissolve in an uncanny fashion, and we understand that he is going to die. And yet, there is, both in this process and following his death, a tone of reconciliation – although questions that arise in the hinterland between life and death remain unresolved. Along with its pauses, interruptions and negations, such questions are profoundly characteristic of Fosse’s language. His 2004 novel Det er Ales (Aliss at the Fire, 2010), includes all of 200 questions in the space of only 70 pages.

A central prose work is Trilogien (Trilogy, 2016), consisting of Andvake (2007), Olavs Draumar (2012) and Kveldsvævd (2014). A cruel saga of love and violence with strong Biblical allusions, it is set in the barren coastal landscape where almost all of Fosse’s fiction takes place. For this highly dramatic and tautly crafted tale, Fosse was awarded the 2015 Nordic Council Literature Prize.

Fosse’s magnum opus in prose, however, remains the late Septology he completed in 2021: Det andre namnet (2019; The Other Name, 2020), Eg er ein annan (2020; I is Another, 2020) and Eit nytt namn (2021; A New Name, 2021). Extending to 1250 pages, the novel is written in the form of a monologue in which an elderly artist speaks to himself as another person. The work progresses seemingly endlessly and without sentence breaks, but is formally held together by repetitions, recurring themes and a fixed time span of seven days. Each of its parts opens with the same phrase and concludes with the same prayer to God.

The first section of the novel addresses the painting that Asle, the narrator, has been unable to complete but which is nevertheless dearest to him. This depicts two strokes, one purple and the other brown, in the form of a diagonal cross, the style therefore appearing abstract. It is as if this opening phrase draws together the different time layers of the work into a single infinite present. Asle’s painting becomes an icon, its emblem of a cross indicating the central theme of death.

There is moreover a dominant doppelgänger motif inscribed in the painted cross. In the opening section of the novel, we are allowed access to Asle’s thoughts as he wanders around the city attempting to rescue his friend and namesake Asle from dying in a snow drift. This other Asle appears as an unhappy, alcoholic version of the Christian artist of the same name, the former possible to interpret as the brown stroke in the painting and the latter as the purple, their fates crossed at the moment of death. The septology is moreover not only Asle’s attempt at reconciliation with his own fate, it is also an elegy through which he mourns the premature passing of his wife, as well as a Künstlerroman dealing with his rather less than successful career as an artist. Ultimately, he is unable to tear himself away from the painting: should he even paint over it in white?

While, in the short play Slik var det (2020), something similar occurs, this time the aging painter’s monologue is only around thirty pages long. This variation on a theme demonstrates Fosse’s consistency regardless of genre. The motif of the wanderer recurs in the play I svarte skogen inne (2023), where a man who has lost all ability to navigate, in a fit of delirium, drives his car into the darkness and disappears. Another variation on the same motif occurs in Kvitleik (2023; A Shining, 2023). Once again, it is the human condition that is Fosse’s central theme, irrespective of genre.

In Sterk vind (2021), referred to as ‘a dramatic poem’, Fosse’s increasing use of imagery and symbolism in his plays becomes apparent. From as far back as the 1986 publication of his first poetry collection Engel med vatn i augene, lyrical language has always served as a great resource in his writing. The recent edition of his collected poetry, Dikt i samling (2021), testifies to the important role poetry has played for him over the years in providing the basis for his elementary diction and sense of the limits of language. Interestingly, Fosse has, in recent years, added to his long list of translations into Nynorsk two modern, lyrical classics: Georg Trakl’s Sebastian i draum (2019) and Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino-elegiar (2022).

Anders Olsson

Chairman of the Nobel Committee

The Swedish Academy