Jan-Werner Mueller

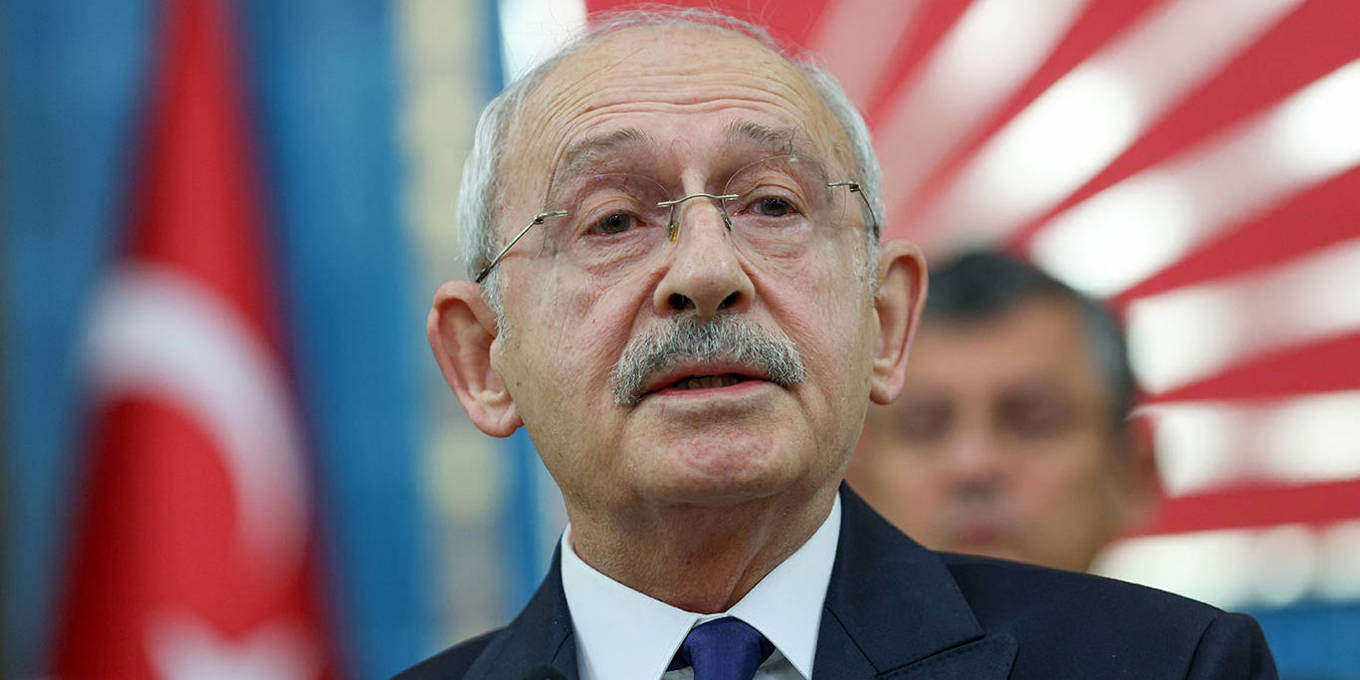

PRINCETON – Following a year of halting negotiations, six of Turkey’s opposition parties have finally united behind a single presidential candidate in the election this May, with the hope of ending Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s increasingly autocratic and repressive two-decade rule. This month, the so-called Table of Six converged on Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the social democratic and secularist Republican People’s Party (CHP), after having sidelined younger, more charismatic contenders such as the CHP mayor of Istanbul, who had recaptured the city from Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party in 2019.

When an authoritarian populist regime is rigging the democratic game, it is common sense that opposition parties must combine forces to stand any chance of winning elections. But such unity, while necessary, is not sufficient for success; in fact, the hardest part comes after the decision to unite.

Opposition parties that unite to remove a particular leader or party – especially “a populist strongman” – must place that imperative above their other programmatic commitments. After all, populist leaders have a proven track record of undermining democracy, and there is every reason to believe they will do even more damage if re-elected.

For example, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has used the immediate aftermath of unfair elections – when the opposition and civil society were utterly demoralized – to ram through controversial policies and engage in culture-war provocations. Budapest’s mendacious memorial to the German occupation, which effectively absolves Hungary of any complicity in the Holocaust, was erected right after the 2014 election.

But, as sensible as this “damage-control” imperative is, it implies that all politics revolves around the strongman. That is exactly what populist leaders want. They excel at using polarization and personalization to their own advantage: “It’s everyone against me, the only leader who truly represents the people.”

Important recent work by political scientists has shown that not everyone who votes for authoritarian populist leaders is ignorant of or indifferent to their undermining of democracy (not to mention corruption, another hallmark of populist governments). But when confronted with an us-versus-them logic and an opposition coalition whose ultimate intentions are uncertain, they might still opt for what they perceive as the lesser evil.

Moreover, united opposition parties tend to settle on candidates who look a lot like the figure they are opposing, only more democratic. Last year, Hungary’s opposition alliance agreed to back a conservative Catholic provincial mayor in its effort to remove the far-right populist incumbent. Similarly, successive Israeli opposition coalitions have sought to beat Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu by putting forward tough center-right figures such as the retired general Benny Gantz. The common assumption seems to be that the restoration of democracy is best overseen by old men. It worked for the Democrats in the United States in 2020, and for Western Europe after World War II, when paternalist figures like Konrad Adenauer and Charles de Gaulle dominated German and French politics, respectively.

Yet such strategies often fail, either because they make the opposition look purely reactive, or (less obviously) because they send defeatist signals that the political parameters established by the ruling populists have become the new normal. In Turkey, the Table of Six has so far yielded to nationalist pressure and rebuffed the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Similarly, the current opposition to Netanyahu’s far-right Israeli government still refuses to include Arab representatives. Strong nationalism – and weak attention to minority rights – is taken as a political given.

Even if anti-populists can unite against a common opponent, changing the parameters of politics is a much more difficult task. Rather than simply appealing to shared dislike of the strongman, they must discuss a broader set of issues and return to questions of policy programs and basic principles. While ideological heterogeneity can be set aside in the name of defeating a populist incumbent, everyone knows that it will return with a vengeance once that task is accomplished, and this common knowledge leaves voters with doubts about how the coalition would actually govern.

To its credit, the Table of Six has outlined structural reforms that would go a long way toward restoring the rule of law and dismantling the hyper-presidential system that has given Erdoğan virtually unlimited powers. Turkey’s Radio and Television Supreme Council and the Council of Higher Education – the kinds of institutions populists specialize in capturing (in the name of “the people,” of course) – would become autonomous again. And by committing to rely on impersonal institutions instead of sultan-style rule, the opposition promises a departure from Erdoğan’s hyper-inflationary (“unorthodox”) economic strategies and erratic foreign policy.

But the promise of “institutionalism” is rather abstract, and it can easily be challenged by highlighting high-profile conflicts over policy and (especially) personnel within the heterogenous opposition alliance. To prevail, opposition leaders will have to demonstrate an underappreciated political skill: framing the terms of the election rather than merely reacting to the other side. They cannot simply assume that corruption will topple the ruling party. They also must stress what has gone wrong and find powerful symbols – not just torturously negotiated policy papers – that give a sense of what a different future would feel like. For the Turkish opposition, the recent earthquake – and the regime’s failures both before and after that catastrophe – will be an obvious reference point in the run-up to the election. But symbolizing a different future is a more demanding challenge.

Jan-Werner Mueller, Professor of Politics at Princeton University, is the author, most recently, of Democracy Rules (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021; Allen Lane, 2021).

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023.

www.project-syndicate.org